Researchers surveyed 344 widowed fathers who had lost a spouse to cancer, and were raising dependent children. Based on responses from surviving fathers, they found that mothers with terminal cancer had substantial worries about their children at the end of their lives, and low levels of peacefulness.

Based on the study findings, researchers reported in the journal BMJ Palliative Care that additional research and improved end-of-life care are needed to specifically help dying parents as well as their families.

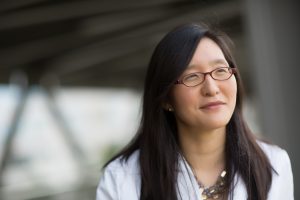

“The major finding of this study was that end-of-life care for dying mothers can be improved, and that they experience significant psychological distress at the end of life, and that this may be related,” said Eliza “Leeza” Park, MD, a UNC Lineberger member and assistant professor of psychiatry in the UNC School of Medicine. “Our research indicates that end-of-life programs need to be more specific and intensified for this particular subgroup that tends to be highly distressed at the end of life.”

According to the surviving fathers, many of the women in the study had not said goodbye to their spouses and the many had not said goodbye to their children.

Thirty-eight percent of mothers had not said goodbye to their children, according to reports from the fathers, and 26 percent were not at all “at peace with dying.”

And 90 percent of widowed fathers reported that their spouse was worried about the strain on their children at tend of life.

However, fathers whose wife had received hospice services were more likely to report that they had said goodbye to their wives, and that their wives had said goodbye to their children.

The study also found links to the mother’s end-of-life experience and the level of depression and grief experienced by the surviving parent. Fathers who reported clearer communication between their wives and their physicians about her condition had lower scores on tests for depression and grief.

“We also found that the depression and bereavement that surviving caregivers experienced was directly linked to the degree of psychological distress that the mother experienced at the end of her life,” Park said. “Therefore, if we were to devise interventions to improve the care of the mother, then we can likely expect that to improve care for the surviving family members as well.”

Based on the findings, the researchers called for additional research into how to better improve care for patients with terminal cancer and their families, and pointed to a need for “substantial improvement” in end-of-life care for dying mothers with cancer.

The study was supported by the University Cancer Research Fund, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, and the National Institutes of Health.

In addition to Park, the other study authors were: Allison M. Deal of the UNC Lineberger Biostastics Core, Justin M. Yopp of the Department of Psychiatry, Teresa P. Edwards of the H.W. Odum Institute for Research in Social Science at UNC-Chapel Hill, Douglas J. Wilson of the UNC Lineberger Biostatistics Core, Laura C. Hanson of the UNC School of Medicine Division of Geriatric Medicine and Palliative Care Program, and Donald L. Rosenstein of the UNC School of Medicine Department of Psychiatry and Department of Internal Medicine.