New cancer drugs taken in pill form have become dramatically more expensive in their first year on the market compared with drugs launched 15 years ago, a University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill study has found. The findings call into question the sustainability of a system that sets high prices at market entry in addition to rapidly increasing those prices over time.

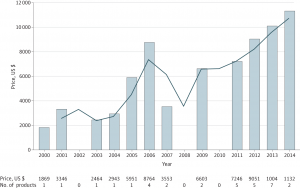

The researchers report April 28 in JAMA Oncology that a month of treatment with orally-administered cancer drugs introduced in 2014 were, on average, six times more expensive at launch than cancer drugs introduced in 2000 after adjusting for medical inflation. Drugs approved in 2000 cost an average of $1,869 per month compared to $11,325 for those approved in 2014.

“The major trend here is that these products are just getting more expensive over time,” said study author Stacie Dusetzina, PhD, a UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center member and an assistant professor in the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy and UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health.

In the past 10 years, there has been a push toward developing orally-administered drugs for cancer patients, but the high prices may increasingly be passed along to the patient, potentially affecting a patient’s access to the drug and their ability to use them, Dusetzina said.

The drug imatinib, also known as Gleevec, was among the drugs with large increases in monthly spending. From the time it launched in 2001 to 2014, the price increased from $3,346 to $8,479, reflecting an average annual change of 7.5 percent.

Dusetzina also explained that the amount that patients pay for these drugs depends on their health care benefits. However, patients are increasingly taking on the financial burden of paying for these high-cost specialty drugs, despite the fact that commercially insured health plans have historically had generous coverage for orally-administered cancer drugs.

“Patients are increasingly taking on the burden of paying for these high-cost specialty drugs as plans move toward use of higher deductibles and co-insurance, where a patient will pay a percentage of the drug cost rather than a flat copay,” Dusetzina said.

In her work, Dusetzina analyzed what commercial health insurance companies and patients paid for prescription fills before rebates and discounts for orally-administered cancer drugs from 2000 to 2014. The data came from the TruvenHealth MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database.

Dusetzina noted that while the study did account for payments by commercial health plans, it did not account for spending by Medicaid and Medicare, which may differ. In addition, only the products that were dispensed and reimbursed by commercial health plans were included, which may have excluded rarely used or recently approved products.