Researchers with UNC Lineberger’s Carolina Cancer Screening Initiative, in collaboration with the Mecklenburg County Health Department in Charlotte, examined the impact of targeted outreach to more than 2,100 people insured by Medicaid who were not up-to-date with colorectal cancer screening.

Mailing colorectal cancer screening tests to patients insured by Medicaid increased screening rates for this population, report researchers at the University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center.

In collaboration with the Mecklenburg County Health Department in Charlotte, researchers with UNC Lineberger’s Carolina Cancer Screening Initiative examined the impact of targeted outreach to more than 2,100 people insured by Medicaid who were not up-to-date with colorectal cancer screening. The project resulted in a nearly 9 percentage point increase in screening rates for patients who received a screening kit in the mail compared with patients who just received a reminder, and it demonstrated that their method could serve as a model to improve screening on a larger scale. The findings were published in the journal Cancer.

The American Cancer Society estimates that more than 97,000 people will be diagnosed with colorectal cancer in the United States this year, and it will result in approximately 50,600 deaths. It is third most common type of cancer in men and women in the United States, and the second leading cause of cancer death.

While colorectal cancer screening has proven effective in reducing cancer deaths, researchers report too few people are getting screened. Current guidelines from ACS recommend regular screening with either a high-sensitivity stool-based test or a structural (visual) exam for average-risk people aged 45 years and older, and that all positive results should be followed with colonoscopy. Despite these recommendation, studies have identified notable gaps in screening rates, including by race, geographic region and other socioeconomic factors. Among patients who are insured, people with Medicaid have the lowest rates of colorectal cancer testing.

“There has been a national push to increase colorectal cancer screening rates since colorectal cancer is a preventable disease, but screening rates are only about 63 percent, and low-income, and otherwise vulnerable populations, tend to be screened at even lower rates,” said the study’s first author UNC Lineberger’s Alison Brenner, PhD, MPH, research assistant professor in the UNC School of Medicine Department of Internal Medicine.

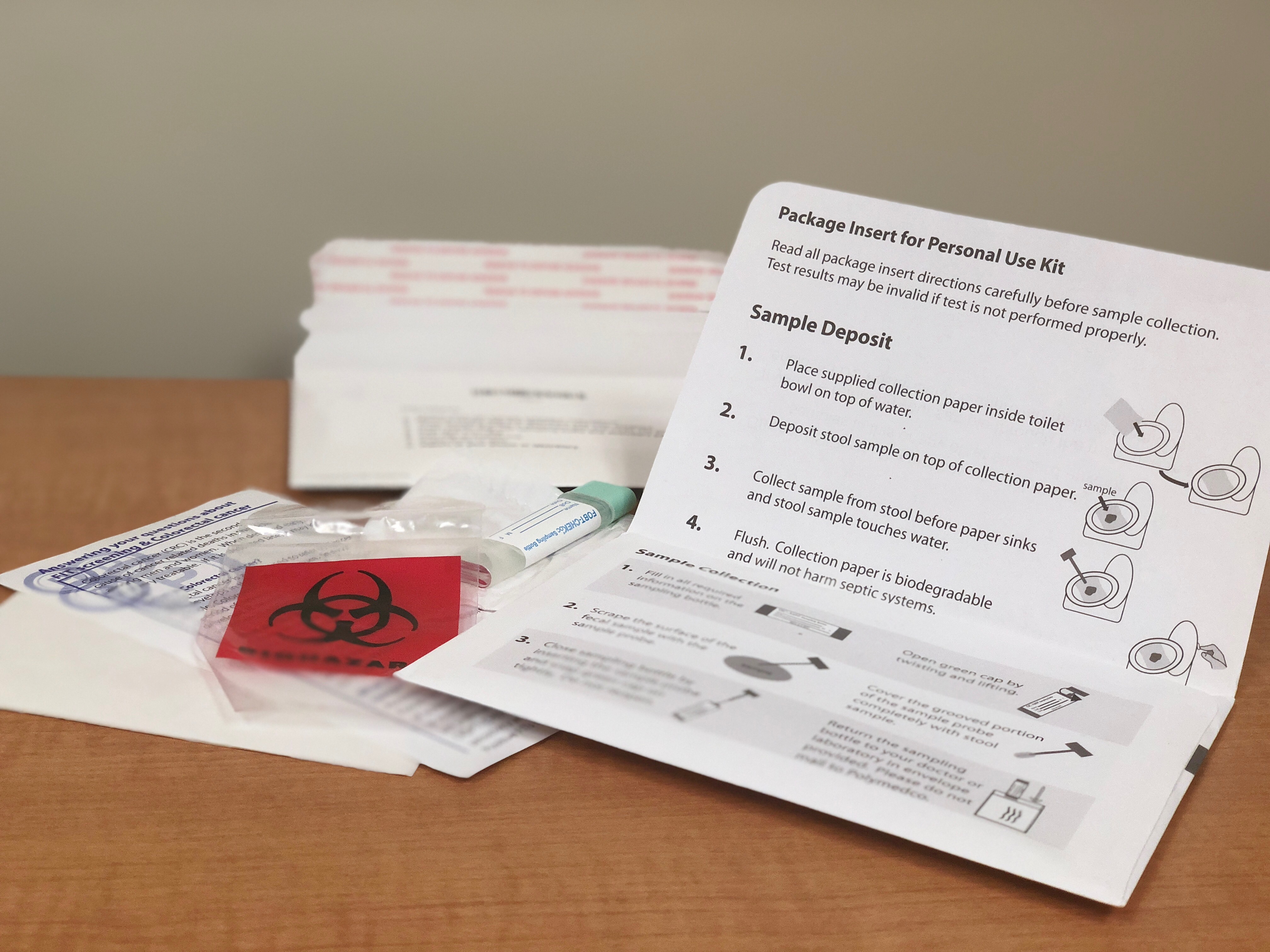

For the project, researchers either mailed reminders about colorectal cancer screening and instructions on how to arrange one with the health department, or reminders plus a fecal immunochemical test, or FIT kit, which can detect blood in the stool – a symptom of colon cancer. The patient completes the test at home and returns it to a provider for analysis. Patients who have a positive FIT kit result will be scheduled for a colonoscopy.

The UNC Lineberger researchers worked with the Mecklenburg County Health Department staff, who coordinated the reminders and mailings and ran the test analyses. They also partnered with Medicaid care coordinators to provide patient navigation support to patients who had abnormal test results and required a colonoscopy.

Twenty-one percent of patients who received FIT kits in the mail completed the screening test, compared with 12 percent of patients who just received a reminder. Eighteen people who completed FIT tests had abnormal results, and 15 of those people were eligible for a colonoscopy. Of the 10 who completed the colonoscopy, one patient had an abnormal result.

“Preventive care amongst vulnerable populations rarely rises to the top of the mental queue of things that need to get done,” Brenner said. “In North Carolina, many Medicaid recipients are on disability. Making something like colorectal cancer screening as simple and seamless as possible is really important. If it’s right in front of someone, it’s more likely to get done, even if there are simple barriers in place.”

Brenner said the study shows the potential to harness resources like the county health department for health prevention services.

“This collaborative and pragmatic quality improvement effort demonstrates the feasibility, acceptability, and efficiency of using existing health services resources and infrastructure, including Medicaid-based navigation to colonoscopy to deliver timely cancer screening services to low income populations,” said UNC Lineberger’s Stephanie Wheeler, PhD, MPH, associate professor in the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health and the study’s senior author.

She said researchers plan to move forward to study whether they can implement their approach on a larger scale, and to understand all of the cost implications.

“This is looking at expanding the medical neighborhood – to harness community resources to target patients and in this case, insured patients, who are maybe not getting this from a primary health care organization, and how to increase screening rates in these types of vulnerable populations,” Brenner said.

In addition to Brenner and Wheeler, other authors are Jewels Rhode, MPH, Jeff Y. Yang, BA/BS, Dana Baker, RN, BSN, CCM, Rebecca Drechsel, MT, Marcus Plescia, MD, MPH, Daniel S. Reuland, MD, and Tom Wroth, MD, MPH.

The study was supported by UNC Lineberger through a Tier 2 Stimulus Award, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the National Cancer Institute Cancer Prevention and Control Research Network. Individual researchers were supported by the National Institutes of Health and the University of North Carolina Royster Society of Fellows.