UNC Lineberger’s Shawn Hingtgen, PhD, and colleagues, in laboratory studies, have converted human skin cells into stem cells that can hunt down and kill human brain cancer, an important step to moving the approach closer to a clinical trial.

UNC Communications and Public Affairs contact: Thania Benios, 919-962-8596, thania_benios@unc.edu

In a rapid-fire series of breakthroughs in just under a year, researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill have made another stunning advance in the development of an effective treatment for glioblastoma, a common and aggressive brain cancer. The work, published in the Feb. 1 issue of Science Translational Medicine, describes how human stem cells, made from human skin cells, can hunt down and kill human brain cancer, a critical and monumental step toward clinical trials – and real treatment.

|

|---|

| Shawn Hingtgen, PhD |

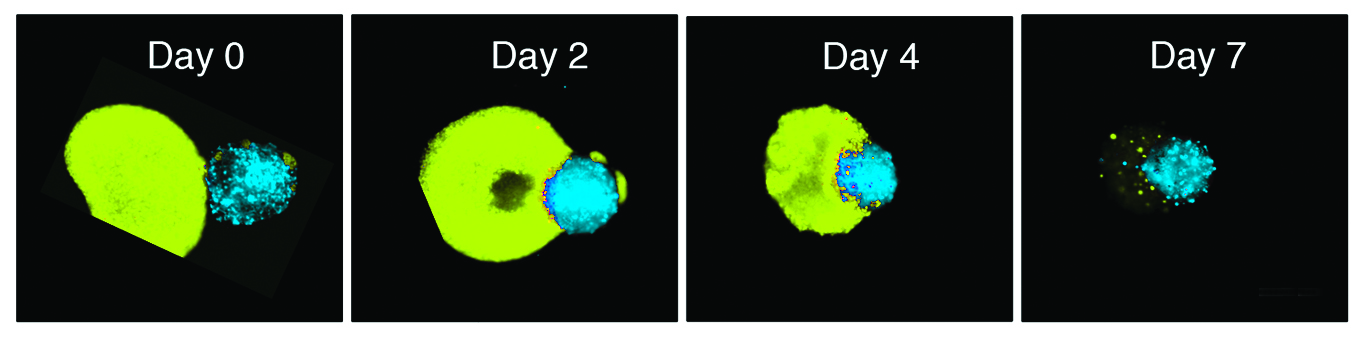

Last year, the UNC-Chapel Hill team, led by Shawn Hingtgen, PhD, an assistant professor in the Eshelman School of Pharmacy and member of the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, used the technology to convert mouse skin cells to stem cells that could home in on and kill human brain cancer, increasing time of survival 160 to 220 percent, depending on the tumor type. Now, they not only show that the technique works with human cells but also works quickly enough to help patients, whose median survival is less than 18 months and chance of surviving beyond two years is 30 percent.

“Speed is essential,” Hingtgen said. “It used to take weeks to convert human skin cells to stem cells. But brain cancer patients don’t have weeks and months to wait for us to generate these therapies. The new process we developed to create these stem cells is fast enough and simple enough to be used to treat a patient.”

Surgery, radiation and chemotherapy are the standard of care for glioblastoma, and that hasn’t changed in three decades. In months, the tumor comes back in almost every single patient, invariably sending tiny tendrils out into the surrounding brain tissue. Drugs can’t reach them, and surgeons can’t see them, so it’s almost impossible to remove all of the cancer, explained Ryan Miller, MD, PhD, a UNC Lineberger member, coauthor of the study and neuropathologist at UNC Hospitals and associate professor at the UNC School of Medicine.

“We desperately need something better,” said Hingtgen.

The key to Hingtgen’s treatment is “skin flipping,” a technology for creating neural stem cells from skin cells that won a Nobel Prize in 2012. The first step is to harvest fibroblasts — skin cells responsible for producing collagen and connective tissue — from the patient and reprogram those cells to become what are called induced neural stem cells, which have an innate ability to home in on cancer cells in the brain.

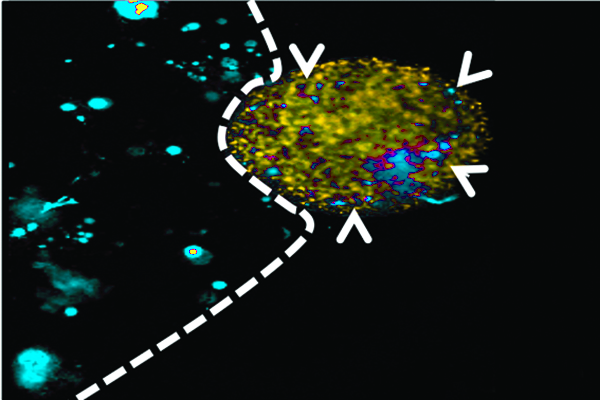

But by themselves, stem cells can only find a tumor and bump up against it – not kill it – so the team had to engineer stem cells that could carry therapeutic agents that the cells can launch at the tumor to kill it.

Hingtgen’s stem cells can carry a protein that activates an inert substance called a prodrug that is given to the patient. The cells can then generate a small halo of drug that is located just around the stem cell, rather than it being circulated throughout the patient’s body, reducing unwanted side effects.

“We’re one to two years away from clinical trials, but for the first time, we showed that our strategy for treating glioblastoma works with human stem cells and human cancers,” said Hingtgen. “This is a big step toward a real treatment – and making a real difference.”

- Juli Bagó, Ph.D., postdoctoral research associate, UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy;

- Onyi Okolie, graduate student, UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy;

- Raluca Dumitru, M.D., Ph.D., director of the Human Pluripotent Stem Cell Core, UNC School of Medicine;

- Matthew Ewend, M.D., chair of the Department of Neurosurgery at UNC Hospitals, Van L. Weatherspoon, Jr. Eminent Distinguished Professor at the UNC School of Medicine, and member of UNC Lineberger

- Joel Parker, Ph.D., associate professor at the UNC School of Medicine, director of bioinformatics at UNC Lineberger;

- Ryan Vander Werff, M.S., sequencing manager, University of British Columbia Biomedical Research Centre;

- Michael Underhill, Ph.D, professor, University of British Columbia;

- Ralf Schmid, Ph.D., a research associate at the UNC School of Medicine.