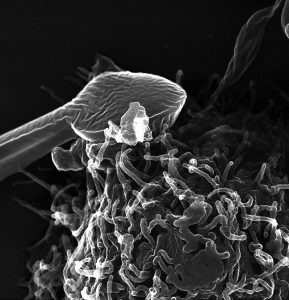

Jack Griffith, PhD, Kenan Distinguished Professor of Microbiology and Immunology and member of the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, has received the Progress in Photography Award from the Photographic Society of America for his work using photo-microscopy with the electron microscope to reveal details of DNA mechanics and organization.

Griffith is the 2021 recipient of the Progress in Photography Award from the Photographic Society of America (PSA), the largest society dedicated to photography. Past winners of the award include Walt Disney, Ansel Adams and Nick Woodman.

Griffith’s lab at UNC focuses on DNA-protein interactions combining electron microscope, biochemistry, genetics, and modern molecular approaches. Here he answers a few questions about his work.

Did you think your work would lead you to a photography award?

No. Not at all. Although there’s been no question in my mind that our work, and the science behind our photographs taken with the electron microscope, is important. And in some cases there are months of effort in a lab that lead to one image. I’ve been obsessive with the quality of these images to the point where I’ve probably driven some of my colleagues nuts. But because our photographs are very striking, it makes a huge difference in the believability of the science story we are trying to demonstrate.

How did you get started taking these pictures?

I did a lot of photography growing up in Alaska, capturing images of wildlife. My passion continued through college and in graduate school I ended up teaching a laboratory class in electron microscopy. The combination of that, plus my background in physics, helped me build the basis of the photography we take today. I would say our laboratory now has done more of this work capturing images of DNA and genetic material than any other lab in the world, and we’ve placed images on the cover of 40 journals.

Why are these images important for the scientific community?

These pictures demonstrate in one image what sometimes took years of research work to discover. They get placed in textbooks and other educational formats that help explain the concepts being depicted, but also may capture the attention of someone who may otherwise have overlooked the material. There are some discoveries that no one would have believed if we didn’t have photographic evidence of them. Science isn’t a matter of hiding away and doing it all yourself. It’s about working with colleagues and friends. We’ve been particularly collaborative at UNC. Around 2,100 pictures have been published in peer-reviewed journals since I’ve been at UNC.

What images have stood out to you?

I’m very particular about these images – they’re almost like my children. I have some big prints of them hanging on the walls in my home. The first picture of a DNA molecule with little DNA polymerase molecules lined up along like a chain of grapes is certainly a very important breakthrough image because it was the first time anyone had seen DNA with proteins bound to it.

Then a number of years later when I was a post-doc we purified little chromosomes from cells that were composed of double-stranded DNA from a virus and they were bound up by the normal chromosomal proteins called histones. These little circular DNA were arranged into 21 little beaded particles and each was separated by a short segment of DNA. That was the first time a structure of these chromosomes had ever been seen or deduced.

Later around 1999 we got some beautiful pictures of DNA arranged into telomere loops (t-loops). Had we not had the electron microscope, no one would have believed that the end of chromosomes are in a looped organization.

How do you feel about winning the Progress Award?

I was very humbled looking at the list of past winners of this award. And one person on that list, Lennart Nilsson, has been my hero for decades for his work with medical videos and photographs of the human body. I’m very pleased for this work – that so many others have contributed to over the years – to have this kind of recognition.

The Progress in Photography Award is the PSA’s highest honor and recognizes a person who has made an outstanding contribution to the progress of photography or an allied subject. In addition to other forms of photography, Griffith enjoys flying airplanes, restoring old cars (Jaguars and Ferraris) and riding horses.

—UNC Health