Zika, the virus currently causing worldwide concern due to its alarming connection to a neurological birth disorder, was discussed as part of a presentation on emerging infectious diseases for the UNC Lineberger-led seminar series titled “Virology in Progress.” Helen Lazear, PhD, a UNC Lineberger member and an assistant professor in the UNC School of Medicine Department of Microbiology and Immunology, spoke about Zika and noted that experts know relatively little about the virus.

The mosquito-borne Zika virus is not new to science, but it’s one that researchers want to know a lot more about especially in light of the recent outbreak, a University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill researcher told virology experts, students and researchers at the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center on Friday.

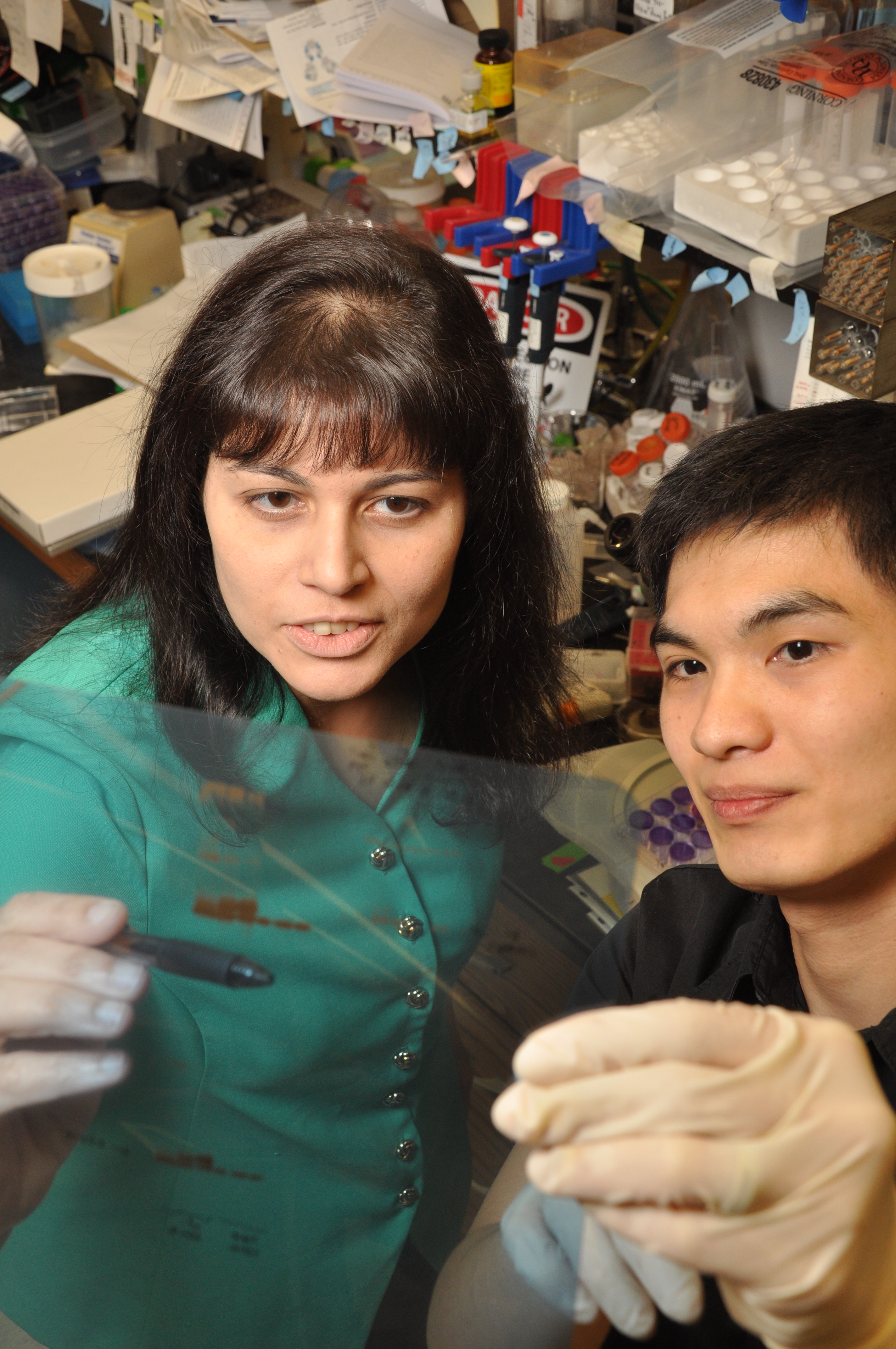

Helen Lazear, PhD, a UNC Lineberger member and an assistant professor in the UNC School of Medicine Department of Microbiology and Immunology, spoke about Zika as part of a presentation on emerging infectious diseases for Virology in Progress, a seminar series hosted weekly by the UNC Lineberger Virology Program in order to spur collaborations between virologists working across campus. At UNC Lineberger, researchers are studying the mechanism of how viruses such as such as HPV, oncogenic herpesviruses and HIV cause cancer in order to generate possible new or better treatments for virally-linked cancers.

“The seminar series serves as a training vehicle for our graduate students and postdoctoral fellows, who study viruses in labs all across the UNC-Chapel Hill campus, including at UNC Lineberger, the School of Medicine, the Gillings School of Global Public Health, the Dental School, and the College of Arts & Sciences,” said Blossom Damania, PhD, the co-director of the UNC Lineberger Virology Program, the Boshamer Distinguished Professor in the UNC-Chapel Hill Department of Microbiology and Immunology, and the assistant dean for research at the UNC School of Medicine.

Zika was first identified in 1947, Lazear said, and caused sporadic outbreaks in the decades following. An “explosive” outbreak on the Yap Island in Micronesia in 2007 preceded the virus’ spread in the region, she said. Then last year, the virus was identified in Brazil. It has rapidly spread in the country, she said. Now approximately 24 countries have reported local transmission of the virus – which is when a person has contracted the virus without reporting recent travel.

In addition to Lazear’s presentation on Zika, Aravinda de Silva, PhD, a professor in the UNC School of Medicine Department of Microbiology and Immunology, spoke on the history of the Aedes aegypti species of mosquito that spreads Zika virus as well as the dengue and chikungunya viruses; Mark Heise, PhD, a UNC Lineberger member and professor in the UNC School of Medicine Department of Genetics and Department of Microbiology and Immunology, spoke on the history and spread of the chikungunya virus in Latin America; and Matt Collins, an infectious diseases fellow in the UNC School of Medicine, spoke on the risk of Zika virus for travelers and potential for transmission in the United States.

In the United States, she said protections — such as the presence of window screens, air conditioning and lower temperatures in the winter season — that have helped control the spread of other mosquito-borne viruses in the United States would likely help prevent the spread of Zika.

“For all of the media attention this has been getting, we know astonishingly little.”

The virus is now circulating in Latin America and in the Caribbean, Lazear said, with two other viruses that are difficult to distinguish clinically. Recent outbreaks have been associated with more severe clinical presentations, including microcephaly in newborns of infected mothers.

Scientists do not yet know the mechanism by which microcephaly is occurring, she said. Lazear reported on planned research to create preclinical models to help understand microcephaly related to Zika infection, as well as to understand mechanisms of viral pathogenesis.

“For all of the media attention this has been getting, we know astonishingly little,” she said.

The seminar was organized by de Silva, Damania said. The Virology in Progress series was launched initially by Nancy Raab-Traub, PhD, a UNC Lineberger member, the co-director of the UNC Lineberger Virology Program and Distinguished Professor in the UNC School of Medicine Department of Microbiology and Immunology.