For the last decade, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has required tobacco manufacturers and importers to report the levels of harmful and potentially harmful chemicals found in their tobacco products and tobacco smoke. The idea was to educate the public and ultimately to decrease tobacco use, but little research has demonstrated if such information can impact on people’s decisions to quit smoking.

A new study from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill has found that smokers who saw messages about tobacco chemicals with associated health risks, together with graphic health images and information promoting quitting, expressed greater desire to quit smoking. In the journal JAMA Network Open, UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center member Adam O. Goldstein, MD, MPH, professor of Family Medicine at the UNC School of Medicine, and Leah M. Ranney, PhD, associate professor of UNC School of Medicine’s Department of Family Medicine, report smokers’ intentions to quit smoking increased almost 10% after being exposed to the messaging.

“Communicating about toxic constituents found in combustible tobacco products, such as formaldehyde, uranium or arsenic, is an innovative but unproven new strategy mandated for the FDA to implement,” said Goldstein, director of the UNC Tobacco Intervention Programs. “We found for the very first time that a strategy utilizing impactful messaging about such chemicals, combined with potent images depicting those messages, may help those still addicted to cigarettes in their efforts to quit.”

About the study

The researchers enrolled 789 adults in a randomized control, longitudinal study to assess whether daily emails containing a range of constituent message elements influenced a person’s intention to quit smoking.

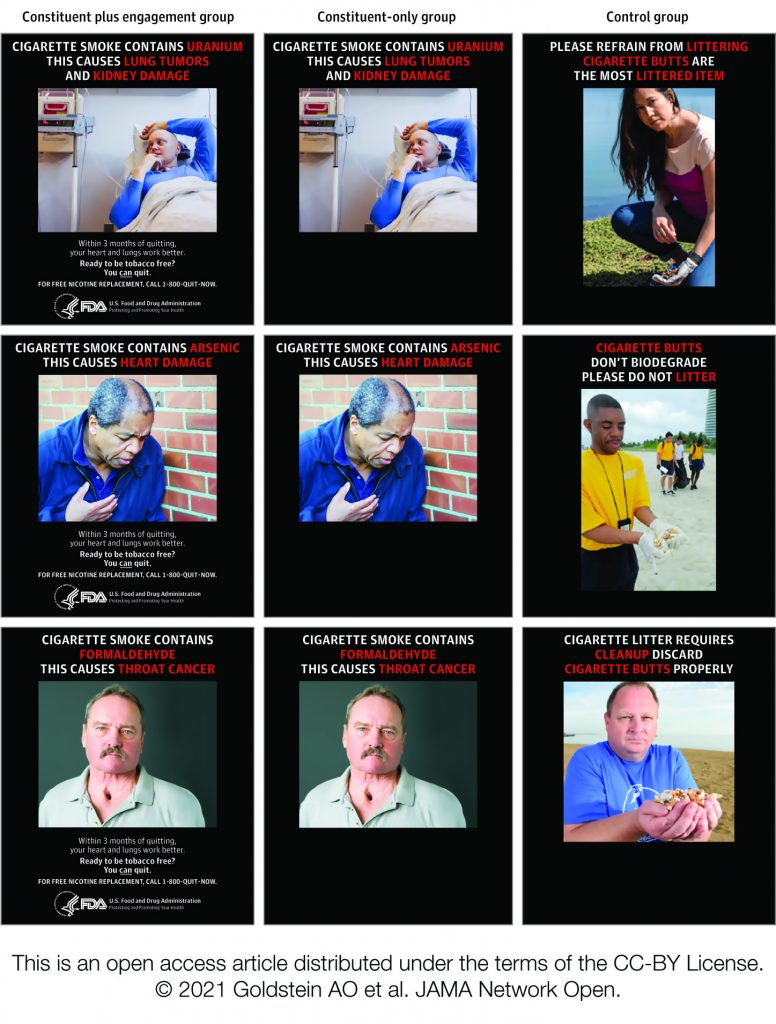

The study tested three conditions— two were experimental and one was the control — with messages on chemicals in cigarettes sent to participants for 15 consecutive days. The first message included a graphic image of a person with a health issue, information on a chemical in the tobacco (lead, uranium, arsenic, formaldehyde or ammonia), a related health problem, a toll-free quit line and the FDA logo. The second included a graphic image of person with a health issue and a tobacco constituent message but not an FDA logo or any quit line information. The third, the study control, included only an image of cigarette butt litter and a message reminding people not to litter.

The smokers’ quit intentions were assessed on the 16th day and then again on the 32nd day. The researchers also tracked the number of cigarettes a person smoked as well as chose not to smoke or put out before it was finished because the person wanted to smoke less.

Goldstein said study participants who received either of the experimental messages were more likely to consider quitting smoking. “Smokers’ intentions to quit smoking increased almost 10% over the short time period that our constituent communication campaign ran in our national sample. Campaigns that run longer and reach millions of smokers will almost certainly stimulate much larger numbers of smokers in the U.S. with intentions to quit.”

The researchers found no significant differences in response to the two experimental messages, suggesting that featuring a tobacco constituent message and image were sufficient to increase smokers’ intentions to quit.

“Our findings support disseminating health messages describing the harmful health effects of five well-known toxins found in cigarettes to help smokers’ motivation to quit,” Ranney said. “Our findings can help inform the FDA as they implement new educational campaigns about cigarette smoke toxins. Those in our study looked at almost two-thirds of daily messages sent over three weeks, and it is really interesting that the more messages they viewed, the fewer cigarettes they smoked.”

The authors noted that while the overall effect was “mild,” quit intentions were higher and cigarettes smoked decreased as the number of messages viewed increased, regardless of condition. “Even a small impact could be meaningful on a population level, particularly if policy-makers use it as a guide to investigate stronger strategies, channels and methods to help those wanting to quit,” they wrote.

Ranney said increasing a smoker’s intention to quit is a critical first step to quitting smoking. “That is what our experimental constituent messages in our study achieved,” she said. “With motivation and support through counseling and with or without medication, many smokers who are motivated to quit can actually quit.”

Authors and Disclosure

In addition to Goldstein and Ranney, the other authors were Kristen L. Jarman, MSPH, and Sarah D. Kowitt, PhD, UNC School of Medicine Department of Family Medicine; Tara L. Queen, PhD, and Kyung Su Kim, MS, UNC Lineberger; Bonnie E. Shook-Sa, DrPH, UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health; Paschal Sheeran, PhD, UNC Lineberger and UNC College of Arts and Sciences Department of Psychology and Neuroscience; and Seth M. Noar, PhD, UNC Lineberger and UNC Hussman School of Media and Journalism.

The study was funded in part by the National Cancer Institute and the FDA Center for Tobacco Products. Noar has served as a paid expert witness in government litigation against tobacco companies.