Aggressive brain tumors are notoriously tough to treat. Many tumors are difficult to reach because they grow deep into the brain. The protective capillary system surrounding the brain, designed to shield it from toxins, can weaken a drug’s ability to kill the tumor cells it’s meant to target. And the complexity of different brain tumor mutations can render some genetic analyses ineffective. These and other factors can make it a challenge for patients and their doctors to decide on the best course of action.

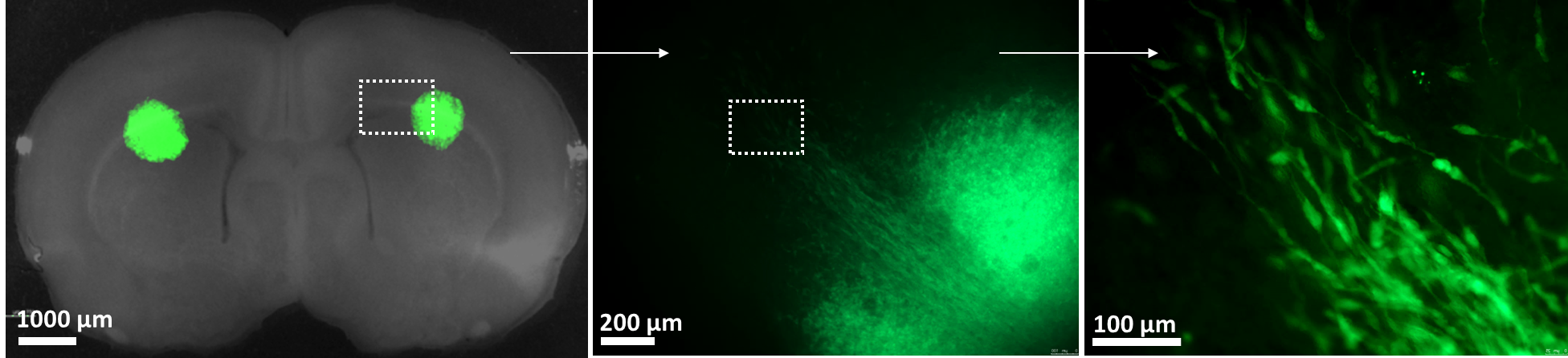

UNC Lineberger scientists have developed a tool called a “slice platform” that may help make those decisions easier. This process, which offers a unique way to keep tumor cells alive outside of a cancer patient, entails removing a few tumor cells from a patient’s brain and placing them on a living slice of rodent brain. (Human brain tumor cells placed in a tissue culture dish will rapidly die. However, human brain tumor cells that embed into the rodent brain slice grow.) Researchers can then simultaneously test up to a dozen different drugs to see which ones most effectively kill the live tumor cells. This highly complex process takes just four days.

The team of scientists and clinicians advancing the development of this technology uses the lab of Shawn Hingtgen, PhD, as their home base. Running point on the innovative project is Andrew Satterlee, PhD, who has a powerful personal incentive to advance this technology: about 16 years ago, as a 20-year-old college student, he was diagnosed with brain cancer. The surgery to remove the cancer was successful, but because his tumor was rare, his doctors could not agree on what kind of chemotherapy regimen would best prevent recurrence. The decision was left with Satterlee and his family, who did a lot of research themselves and consulted with outside experts for advice and guidance.

“I feel so lucky to be developing this tool because I know how helpful it can be. If there was a better way to decide what drugs I needed, we would have used it,” said Satterlee, associate director of the Brain Slice Technology Program. “If this test can offer an objective data point and ease the burden on patients, it can be a really important puzzle piece to help physicians make care decisions.”

Slice technology has been previously used to successfully study stroke and neurodegenerative disease, and around 2016, researchers like UNC Lineberger’s Al Baldwin, PhD, Kenan Distinguished Professor of Cell Biology, began exploring it to study cancer. But putting live patient tumor tissue onto the brain slices so they can grow is a novel idea, and the research team’s excitement about the possibilities is palpable.

“We’ve realized that putting fresh tumor cells on the slices allows them to survive unlike they do anywhere else,” Satterlee said, adding that embedding high-grade or low-grade tumors, or primary brain tumors versus metastases, has yielded similarly exciting lab results. “We haven’t found a tumor type yet that won’t grow on the slice.”

In May, the research team published their key findings in Cell Reports Medicine. They also patented their process and, thanks to a grant from the UCRF, are recruiting patients for a feasibility clinical trial that will take the first steps toward validating the brain slice as a clinical tool to help guide the treatment of patients. Through this trial, the researchers hope to optimize the testing process, find a correlation between their test results and the patients’ clinical responses, and collect robust data that could eventually be submitted to the Federal Drug Administration to help their technology gain approval for clinical use.

“It is really hard to get funding to bridge that translational gap from basic science into the clinic, and the UCRF was able to step in and bridge that gap,” said Hingtgen, professor of pharmacoengineering and molecular pharmaceutics at UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy and professor of neurosurgery at the UNC School of Medicine. “The feasibility trial is the first full deployment of this system in the clinical setting, where we can take the critical first steps toward showing that the system can really help patients.”

Assistant Professor of Neurosurgery Dominique Higgins, MD, PhD, is the highly skilled neurosurgeon who does most of the clinical procedures to remove patients’ tumor cells for the brain slice team. His expertise in cell biology complements Satterlee and Hingtgen’s pharmacology backgrounds, enabling the team to fully consider the intricacies of how this tool should ideally work in a clinical setting.

A specialist in brain tumor treatment, Higgins is starting a separate clinical trial using brain slices to study ferroptosis, a type of cell death triggered by removing certain amino acids from the diet. His previous research uncovered that glioblastoma cells are susceptible to ferroptosis; he hopes that using brain slices can help identify therapies to promote or accelerate that process.

“This is a high-throughput way of testing new agents in a native microenvironment that a tumor would typically see,” Higgins said. “It’s a great opportunity to study drugs that target tumor metabolism, and brain slice technology can help answer some of these questions. It’s also exciting to think about applying this technology not just to brain tumors, but to other cancers.”

To that end, the research team includes translational researchers like David Kram, MD, MCR, FAAP, an associate professor of pediatric hematology and oncology who is working toward new therapies for pediatric brain tumors, and clinician-researchers like Victoria Bae-Jump, MD, PhD, professor of gynecologic oncology, who is exploring the possibilities of using a similar slice platform to test treatments for ovarian cancer. Given the platform’s potential to accelerate drug development, the team also collaborates with outside academic institutions, organizations and pharmaceutical industry partners.

“It comes back to partnership. We all have different tools and expertise, and it’s been amazing to watch everyone come together and work so well as a team,” Hingtgen said. “In the end, the goal for all of us is ultimately to improve outcomes for patients.”